Wrestling with Hospital Costs

How the battle to control cost inflation created today's hospital reimbursement model

Cuts to Medicare seem to dominate healthcare policy news every few months — with proponents of small government and budget cuts seeking to gut the program citing its rising costs. Typically, these cuts to Medicare take the form of cuts to the amount that hospitals and physicians are reimbursed by the federal government for medical services.

The story of how the prospective payment system (PPS) came about is crucial to understand incentive structures hospitals navigate around and how tricky it can be to change these systems.

Before PPS

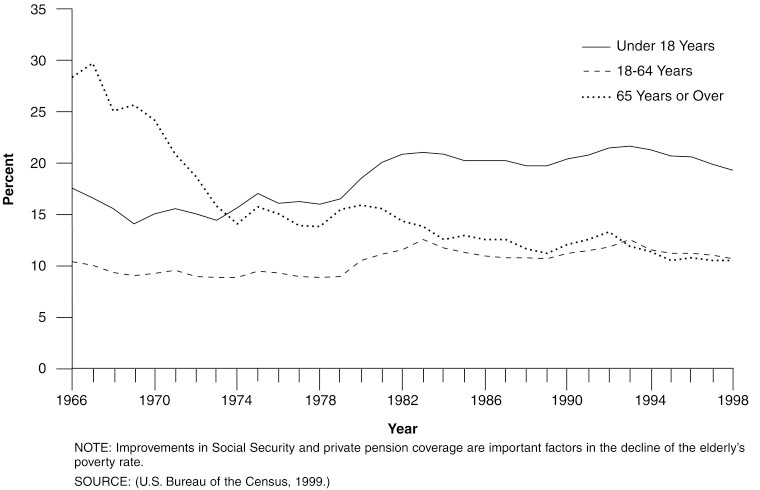

The 1965 Social Security Amendments created Medicare, which covers healthcare for most Americans over the age of 65. As an interesting sidenote, check out the following chart on poverty across different age groups from 1965 through 1998. It’s not enough to say that Medicare caused a drop in senior poverty, but the correlation is quite strong.

The law mandated that healthcare providers would be paid with cost-based reimbursement, such that Medicare pays the cost of a treatment plus 2%. This generous model was inspired by the system developed by Blue Cross/Blue Shield and was favorable enough to gain the widespread acceptance of Medicare insurance by providers across the country.

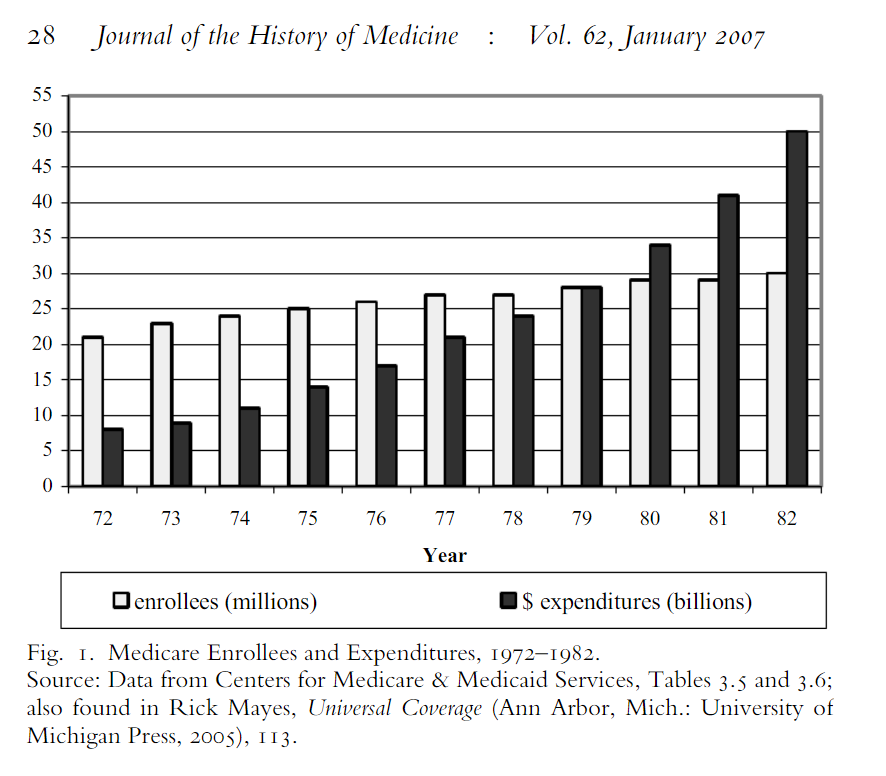

Older Americans, suddenly with a way to afford healthcare services, started seeing the doctor more, and healthcare service utilization ticked up as part of this induced demand. However, doctors could also charge the federal government what they considered necessary to reimburse the cost of delivering care.

The new payer in the market could be charged to pay for higher reported costs which gave hospitals greater revenues, and these hospitals pursued aggressive investments to grow and compete with other facilities.

One result of the SSA’s [Social Security Administration’s] desire to have the medical community embrace Medicare was that doctors’ “customary, prevailing and reasonable” fees — the criteria on which the program based its reimbursement — rose precipitously. Young doctors began billing at unprecedented levels, and the SSA paid them. When older doctors saw the behavior of their younger associates, they too raised their fees.

Source: The Origins, Development, and Passage of Medicare’s Revolutionary Prospective Payment System

There were limited means to control these rising costs. After all, many patients do not truly understand what care is necessary and what is not. When Medicare is paying a large share of these services, it is not shocking that initial cost projections severely underestimated the increase in the cost of healthcare.

Attempts at Cost Control

By the 1970’s, the public’s focus on healthcare went from concerns about longstanding shortages of healthcare services and coverage to an anxiety about the solvency of the Medicare system and reining in rising costs.

The 1972 Social Security Amendments expanded what Medicare covered for — end stage renal disease, nursing homes, and so on — but it also was one of the first attempts by the federal government to curtail costs with Section 223.

The amendment section defined what constituted a “reasonable cost” for reimbursement. Costs from that point were differentiated between routine and ancillary costs, the first of which would be limited. The idea was that ancillary services and costs depended on the sickness of the patient, and a doctor was more likely to charge more if there was actually more resources required to treat for that. Routine costs associated with maintaining the facility and treating any patient, on the other hand, were considered costs that Medicare could limit how much it reimbursed for.

“We understood that people might be sicker and have different ancillary costs, but by God the routine or ‘hotel’ costs ought to bear some similarity to all other hospitals.”

John Mongan, Senior health policy advisor to President Jimmy Carter

After Nixon’s Economist Stabilization Program ended in 1975, these limits took hold and led to some reductions in cost inflation, but hospital administrators learned to take advantage of the definition of “reasonable” costs.

Essentially, the hospitals kept redefiningwhat was ‘routine’ and what was ‘ancillary,’” explains Altman. “Forexample, they would take nurses and change them into ‘respiratorynurses,’ which made them a fully reimbursed ancillary cost.

Stuart Altman, Health policy advisor to President Richard Nixon

The Carter administration came to the White House in 1977 with unrelenting pressure to find out new strategies to curb costs.

“From 1974 to 1977, hospital costs increased at an annual rate of approximately 15%, more than double the economy’s overall rate of inflation.”

Carter proposed the imposition of a nationwide 9% cap on hospital price growth, citing challenges to balance the federal budget to justify the otherwise aggressive approach. The American Hospital Association (AHA) backfired and got key Democrats in Congress to oppose the proposal in Congress, promising instead to voluntarily reduce cost inflation. There was a short-lived success, with cost inflation stepping down to 12.8% in 1978.

The AHA and American Medical Association (AMA) banded together to kill future proposals by Carter to rein in costs. Some interesting dynamics about the politics of these proposals are important to note.

Virtually all Republicans opposed Carter’s plan as excessively complex and an overly intrusive violation of the private sector by the government at a time when deregulation was rapidly gaining popularity. Democrats were split. Urban Democrats generally favored the president’s plan, but Sun Belt and southern Democrats from areas with growing populations were less enthusiastic. Many of them thought that Carter’s plan would restrain the growth of hospital revenues in an inequitable manner that would lock southern hospitals into an inferior quality level relative to their northern counterparts (the “fat will get fatter,” critics charged).

Instead of passing proposals, Congress relied on promises from hospitals to abide by voluntary cost containment. When Republicans took over Congress and the White House in the early 1980’s, pressure continued to mount to contain costs, and the Reagan' administration’s Secretary of Health and Human Services Richard Schweiker paradoxically pursued government activism as the best way to control healthcare costs.

The 1982 Tax Equity and Fiscal Responsibility Act (TEFRA) closed a number of tax loopholes unrelated to Medicare payroll taxes, but it also capped Medicare payments growth for hospital discharges for three years. It also created a new paradigm for federal regulation of providers — instead of limiting cost growth for all payers (Medicare, Medicaid, and private insurance), TEFRA only set rules for Medicare.

TEFRA also called for the Secretary of HHS (Schweiker) to come up with a new proposal for prospective reimbursement, which would reimburse hospitals according to certain diagnoses of patients instead of with a cost-based model. The AHA, fearing the intense price growth caps of TEFRA, cooperated in new negotiations.

1983 saw Social Security fail a bankruptcy crisis, and as part of a bailout bill came the new PPS system.

Where Are We Now

The introduction of PPS curtailed hospital price inflation significantly. Instead of being able to bill for what the provider deemed a reasonable cost, hospitals were being paid fixed amounts for certain diagnoses. That means that a hospital’s profit margin is tied to how quickly and cheaply it can discharge a patient, and it could be argued that maybe this PPS system limits the quality a hospital is incentivized to give its hospitalized patients.

Because the introduction and subsequent reforms to PPS focused only on what Medicare pays for medical services (while aiming to pay less), hospitals with enough local market control can now afford to charge private insurers much higher amounts. This means exorbitantly higher costs for private payers that just pass those along to health plan members through higher premiums, deductibles, and co-pays.

On the other hand, PPS in rural America makes no sense. Rural patients simply cannot drive enough volume to make a per-discharge reimbursement model sustainable without significant reductions in available services compared to what an urban hospital can afford. The critical access hospital (CAH) model was designed to reintroduce a modified version of cost-based reimbursement to some rural hospitals, but even this newer model is not always sustainable.

Thank you!

I am trying to encourage my colleagues in the industry to build safety by design.

I wrote this article recently but it needs updated information. I think the payers are going to soon realize the hidden cost of poor medical device safety which may impact the top line for many companies. This is the premise of my argument.

https://open.substack.com/pub/naveenagarwalphd/p/why-we-need-a-stronger-focus-on-medical?r=1bqvx&utm_medium=ios&utm_campaign=post

Thank you for sharing this historical perspective. Very informative. I work in the medical device industry. Appreciate if you can consider an article about reimbursement policies for medical devices and who pays for recalled or defective devices.