When the Big Fish Bargain

Medicare can now negotiate for drug prices. What impact does that make for Americans?

From this year, the federal government is initiating negotiations for setting drug prices that will take effect from 2026. This is the result of years of lobbying by healthcare reformers and the passage of the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act (IRA). So what about this is going to reduce the price of drugs, and how soon will this end up saving Americans money?

Medicare’s Drug Program

As the largest public health program in the country, Medicare covers most Americans over the age of 65 (as well as others with specific medical conditions). Membership in late 2021 was almost 64 million people, quite a significant portion of all 330 million Americans.

To organize the types of benefits given by the program, there are different “parts” to it. In Traditional Medicare, members get their coverage directly through the federal government. Part A covers inpatient care (mostly hospitalizations) while Part B covers outpatient services like doctor’s visits and specialty services. Almost half of members on Medicare are on an alternative Part C, more commonly known as Medicare Advantage (MA). These plans are administered through private insurers that sell plans offering Part A and B services in addition to other benefits (like dental and vision).

During the 90’s and early 2000’s, the rising cost of prescription drugs became a key concern of Medicare members. In response, lawmakers under the Bush administration passed the Medicare Modernization Act of 2003 (MMA). It added Medicare Part D, and optional supplemental health plan that Medicare members may pay monthly premiums for in exchange for better access to lower cost drugs.

Public reception ranged from muted to bad. One poll found 47% of seniors opposed the changes while only 28% approved.

A number of restrictions on the new Part D plans reflected the loads of lobbying that shaped the bill and its poor popular support. These plans were only to be purchased through insurance companies, and the federal government was entirely banned from negotiating the prices of drugs on any Part D plans. Insurers, on the other hand, had the ability to bargain.

As a side note, Representative Billy Tauzin, a chief architect of the MMA, left Congress shortly after the bill was signed into law and took on a role as the chief lobbyist of Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA), the primary pharma lobbying group in Washington. His salary was rumored to be $2M annually.

Bargaining Power and Pricing

With larger market power, a firm typically gains an upper hand negotiating lower prices. They can offer volumes that may offset smaller margins for the counterparty, and this phenomenon has been demonstrated in practice. In areas where a single insurer has more market power, they can negotiate lower prices with hospitals for certain medical services in their territory.

In fact, the same Commonwealth Fund study found that the power of an insurer can even bring down the price of healthcare providers with regional monopolies.

From the drug pricing perspective, insurers negotiate with drug manufacturers, usually through middlemen called pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs). In this process, the insurer devises a formulary, which sets the list of drugs that an insurer will cover, how much it will pay the manufacturer, and how much the member must pay out of pocket.

Architects of the MMA claimed that they wanted to prevent federal involvement in negotiation because private insurers already had experience setting formularies. This of course, ignores the fact that Medicare had been negotiating prices for hospitals and doctors for decades before 2003.

Given significant pharma lobbying during the passage of the MMA, it seems that the industry pushed for the ban on the federal government negotiating to enable setting higher prices on the comparatively smaller players of private insurance.

Repealing the ban became a focus of President Biden’s healthcare agenda, and the Inflation Reduction Act amended the MMA’s “non-interference” clause. It gave the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services to negotiate with a handful of expensive brand-name drugs.

Down the Road

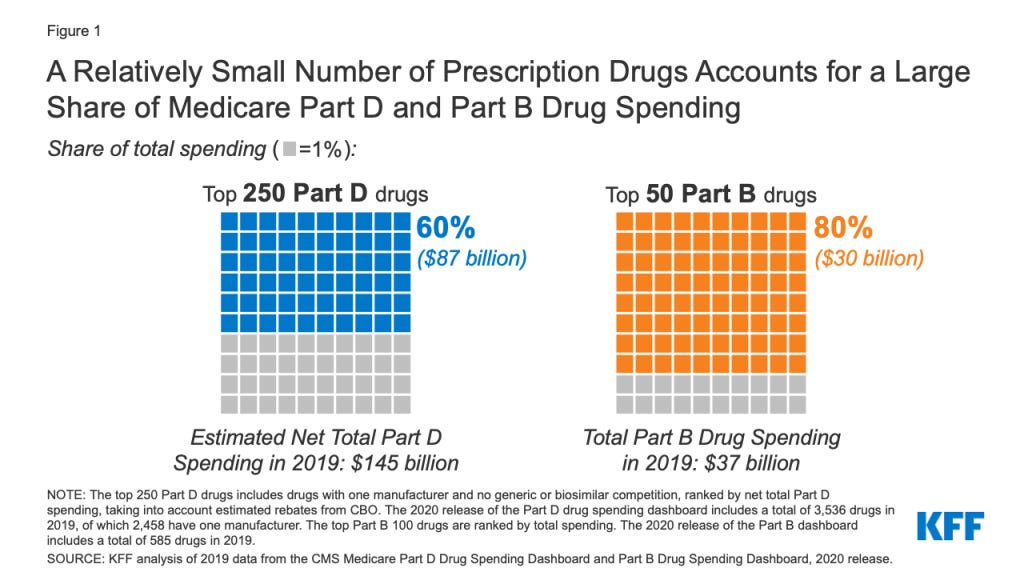

A small number of drugs account for large swaths of spending on drugs in the Part B and Part D programs, so even though the government is only negotiating for a few drugs, it can bring down total spending by billions annually.

From 2026, Part D will set a maximum negotiated price for 10 drugs in 2026, 15 more in 2027, and it will keep adding drugs in following years. From 2028, these negotiated maximum prices will also be in effect for Part B members, meaning some may not need to subscribe to the extra Part D plan.

Negotiations will start this year, and the penalties for pharma companies refusing to engage in negotiations are tough. Remember, Medicare has significantly more bargaining power than any single private insurer, which will likely lead to lower negotiated rates. To manufacturers tempted to refuse negotiation, they can face either aggressive tax penalties (65-95% of US product sales) or removal from coverage by all Medicare plans, which means significantly lower revenue.

These measures will not allow the federal government to negotiate for all drugs, at least by the current wording of the law. It’s important to see what these negotiated maximum prices will be set to, and there will likely be a close eye on how private insurance for younger people will change prices paid to pharma companies. There’s also always the risk that this power of Medicare will be challenged and struck down in the federal court system, like many measures of the Affordable Care Act.