The Little Known Deterrent of the Opioid Crisis

How some states' laws from the 60's spared them from the worst of the crisis

The opioid crisis is one of the pressing public health crises of the modern-day US. What started as a concerning trend of over-prescription evolved into an explosion in abuse of chemically similar drugs like heroin and fentanyl.

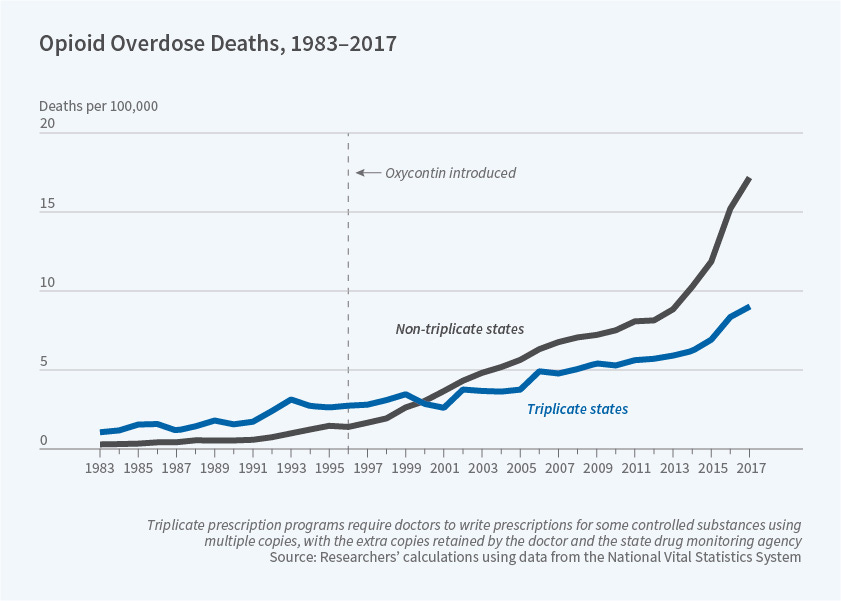

Yet, when assessing the geographies that were most affected by the opioid crisis, it becomes clear that some states were hit harder than others, and that’s by no mistake. Through prescription drug monitoring programs, a handful of states managed to avoid facing the worst of the national crisis, and it’s a valuable story to review when thinking about the implications of variation in state-level health policy and how businesses may take advantage of them.

A Quick Intro to Opioids

Opioids are a class of drug that are known for their ability to reduce sensations of pain. These drugs share chemical properties to the naturally-occurring drug opium and includes naturally occurring products like morphine and codeine, with more artificial forms like methadone and fentanyl.

These drugs bind to receptors that are largely located in the nervous system (brain and spinal cord) and digestive system (including stomach and intestines). When bound to receptors in the spinal cord, the opioid can block the transmission of sensations of pain from nerves through the body to the brain. Receptors in the digestive system can explain why many may experience indigestion when on opioids, and in the event of an overdose, opioids bind to receptors in certain parts of the brain in a way that can trigger seizures, spasms, and even stop breathing.

Some individuals may also experience euphoria when on opioids, because it can trigger neurons which produce the “feel-good” chemical dopamine. Through prolonged use, opioids can build a physical dependence with the user, which is typically how individuals experience substance abuse.

OxyContin and Purdue

Following the ban of heroin in the 1920’s and through the 1980’s, there was a hesitance from physicians to prescribe opioids due to concerns of addiction, despite the entry of drugs like Vicodin and Percocet had entered the market during the 70’s.

Attitudes began to shift, fueled by a notable letter to the New England Journal of Medicine which stated that opioids administered to hospitalized patients were not associated with high rates of addiction and a large push in the early 1990’s to make pain management a priority of physicians.

In 1996, the infamous Purdue Pharma entered the market with OxyContin, a variant of the compound oxycodone with an extended period of time for it’s release into the body. The company’s sales strategy was aggressive, conducting 40 pain management training conferences for physicians across the American southeast and southwest between 1996-2001. Salespeople, who were compensated handsomely, told physicians that OxyContin was unlikely to cause addiction — a message conveyed across videotapes, brochures, and the Partners Against Pain campaign it ran.

“…by 2001 it had become the most frequently prescribed brand-name opioid in the United States for treating moderate to severe pain”

”The Promotion and Marketing of OxyContin: Commercial Triumph, Public Health Tragedy”

Over-prescription of the drug, and as a result similar opioids, spiraled into the wider opioid crisis over the next ten years. It wasn’t long until the company started facing lawsuits over aggressive marketing for a product which was causing an uncontrollable number of overdoses. The story of the next stages are extensive — from the first lawsuits from West Virginia and Kentucky, to the 2007 indictment of several executives, and the eventual filing for bankruptcy.

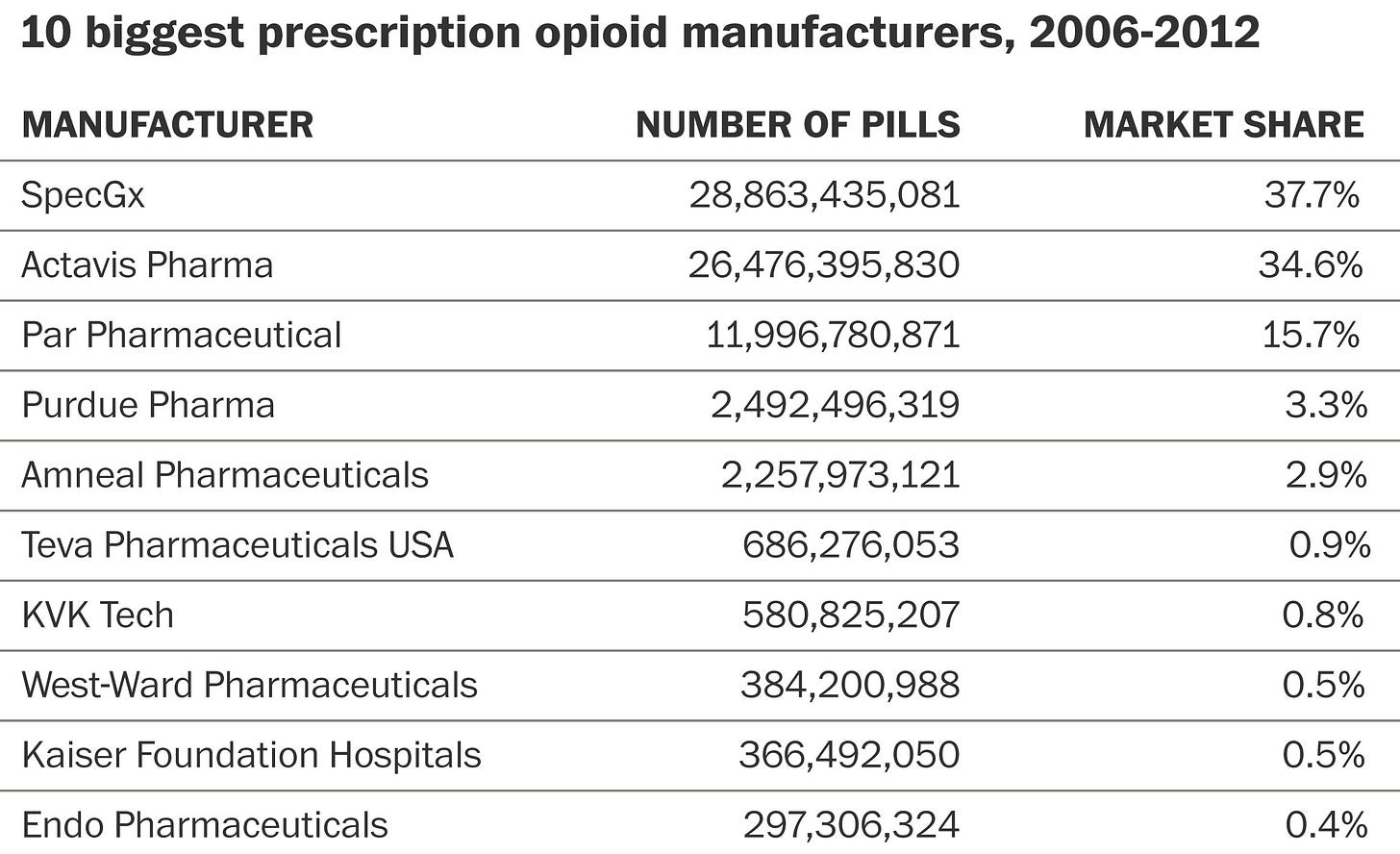

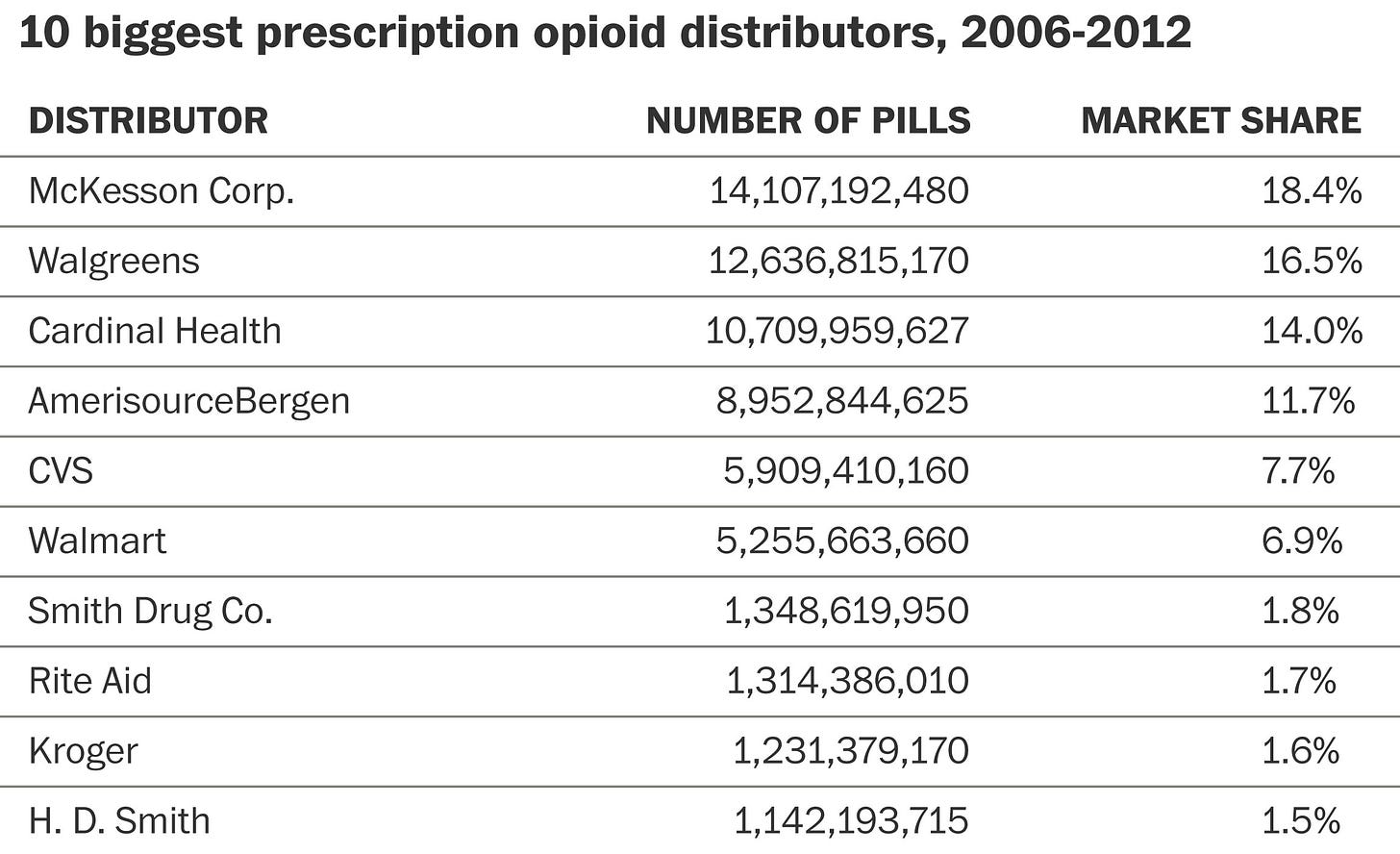

Purdue, was of course, not the only company selling opioids, and it couldn’t have been done without the help of distributors — once again, there are countless stories of lobbying, marketing, and lawsuits.

Triplicate Drug Programs

A working paper from the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) highlights one particular piece of public policy which stemmed the effects of the crisis in its early days.

The NBER paper highlights the so-called triplicate prescription program, an early type of prescription drug monitoring program (PDMP). Under this program, which largely happened before the advent of electronic monitoring systems, physicians had to write three copies of each prescription of a Schedule II drug.

One copy would be kept by the physician, one kept by the pharmacy dispensing the drug, and the third copy going to the state monitoring agency. The first of these programs came about in California during 1939. The state would shutter the program in 2004 following a transition to electronic recordkeeping.

From 1961-1988, Idaho, Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, New York, and Texas followed suit in setting up similar programs. Of them, Indiana and Michigan ended their programs before OxyContin’s launch.

Interestingly, internal Purdue Pharma documents repeated that physicians in “triplicate states” were less likely to be willing to prescribe OxyContin, because it was a Schedule II drug that would require triplicate prescriptions. The combination of scrutiny from the government and a higher administrative burden was simply not worth it for many of these physicians.

The company deemed these regulations a barrier to market entry and focused efforts on “non-triplicate” states with such programs. The results are staggering.

It serves as a clear reminder that state-level policy has very real impacts on the business strategy of various companies. For healthcare companies harvesting user data, it becomes clear why they may stray away from states like California which has the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA). On the other hand, companies focused on increasing access to rural healthcare face higher barriers to entry in states which haven’t expanded Medicaid in accordance with the Affordable Care Act (ACA), which by proxy gives many rural hospitals a life-saving boost in revenues to keep their doors open.