Prior Auth, UM, and Tech's Arrogance

Tech won't fix prior auth because prior auth need not exist in the first place

Prior authorization, being at the top of every healthcare provider’s mind these days, has garnered attention as a time-consuming process in which patients fall through the cracks and get denied care. The practice of prior authorization refers to an approval process that providers must engage in with health insurance companies to ensure that patients have the approval for outpatient procedures like labs, imaging studies, and many surgeries. Payers conduct some form of review and may approve or deny the request citing a lack of documentation that the procedure is “medically necessary”. Without that approval, the provider’s claims will not be paid by the payer.

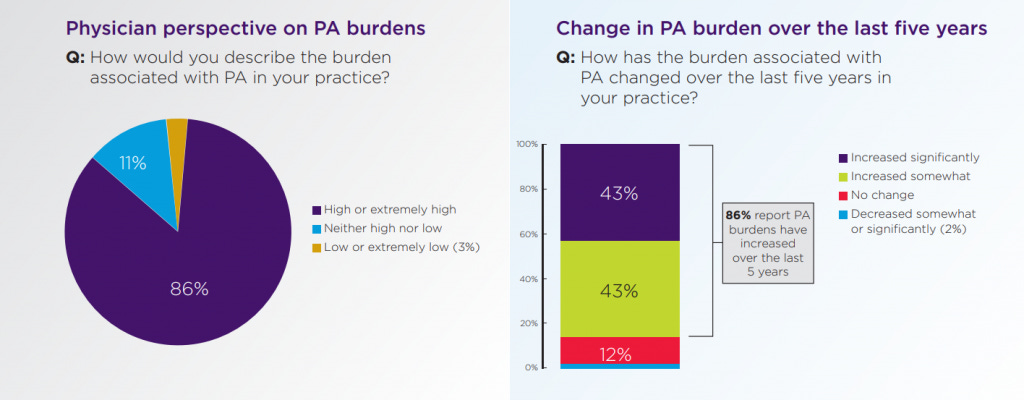

Inability to complete the prior auth process has disastrous effects. Patients face delays to care (or may be denied it altogether) while clinicians face yet another administrative task that adds to burnout inducing workloads they face.

It’s a problem well-known to clinicians and simple to understand from a high-level — hence venture capital has jumped on the opportunity to pour millions into startups promising to solve problems of prior authorization. The list of companies raising capital to solve this problem goes on and on — Cohere, Basys.ai, PriorAuthNow, Rhyme — and robotic process automation (RPA) firms have leveraged their technology to try automate prior auth workflows.

Prominent venture capital firm a16z boasted the capability of AI technology to potentially address this prevalent obstacle to care.

Potential for 10x performance with AI

Relatedly, areas in which humans are prone to error or are generally slow and inefficient (even when supported by software products) are most likely to benefit from AI approaches. For instance, in prior authorizations, a recent AMA survey found physicians and their staff spend approximately 14 hours per week completing PAs

Source: a16z

Can automated workflows and integrated health IT help alleviate the pains of prior auth and improve a provider’s cash flow? Yes. Getting clinicians off administrative tasks to cross reference necessity criteria, pull medical records, log into payer portals, upload documents frees up time to see patients and ensures that procedures can be scheduled faster with fewer patients losing interest.

The assumption tech companies take on prior auth is that it is a painful yet non-negotiable process. To the hospitals and practices that cannot justify prioritizing automation technology over meeting payroll, there is no luck. It also creates perverse incentives to keep prior authorization instead of revamping the way payers control cost, because all of a sudden you have large tech companies whose bread-and-butter is selling a service to a problem that does not need to exist. Buy the technology or die.

UM and the Business of Health Insurance

Prior authorization is part of the process of utilization management (UM). The premise of UM is that with healthcare costs on the rise throughout the system, medical procedures must be evaluated for whether it is medically necessary for a patient to receive a treatment. This process is supposed to consider whether the patient’s medical history correlates to a diagnosis being severe enough to justify certain tests and procedures or ensuring that a physician has pursued other treatment options before choosing more expensive ones.

This process is often encouraged and enforced by payers. One example of a UM strategy is high-cost case management wherein the payer may assign case managers and navigators to members with particularly complex or severe healthcare conditions. Through supporting care coordination, review of social needs, and engagement with the patient, the premise is to control the costs that may be associated with these members. This is not without merit. In 2019, 5% of patients accounted for nearly 50% of spend in the United States.

In the context of prior authorization, the clinician must submit a request to authorize a procedure for a member of the insurance plan. As the payer, they can simply deny reimbursement for the healthcare service if that member never got such an authorization. This is a process which has gotten payers into hot water over denying care to patients clearly in need of treatments ranging in purpose from diagnostic and preventive to therapeutic and surgical. Assessing a subset of Medicaid enrollees , 1 in 5 patients mentioned running into challenges accessing care because of utilization management.

One interesting factor to note is that Traditional Medicare does not use prior authorization as a part of UM. Prior authorization is largely perpetuated by private payers including those that administer benefits for government programs. Prior authorization by Medicare Advantage (MA) plans is considered the most egregious given that they have older, sicker populations requiring more healthcare services which end up getting delayed or denied. Even with Medicaid, a program intended to serve the low-income populations of states, private payers administer coverage through managed care. An interesting note — five Fortune 500 publicly-traded firms have managed care agreements in more than 12 states.

Going a step further, UM has even been applied to admission of patients to inpatient hospitalization. As a general rule of thumb, inpatient hospitalization refers to stays lasting 48 or more hours whereas observation stays (classified as outpatient and lower cost) are anything less. Typically, sicker patients need to be in the hospital longer, but many private payers have a dedicated UM process for hospital admissions. In 2017, an evaluation of patients across 9 California hospitals found that 8.4% of patients were denied coverage for hospitalization.

In fact, when talking about the exorbitant hospital bills many patients face, part of these surprise multi-thousand dollar bills can be attributed to payers refusing to cover several days of a patient’s stay on the grounds that it was not “medically necessary”.

Of course, this has fantastic financial implication for payers who can simply deny care, do not have to reimburse clinicians and get to retain a greater share of revenue from premiums. Aggressive utilization management practices compounded by untested predictive algorithms continue to deny access to care — especially for seniors.

The Process

The UM process for providers is atrocious, to say the least. As a provider, one must know what procedures for which payers require prior authorization. In the context of hospitalists, there must be an awareness of admission criteria by payers for patients who may need inpatient hospitalization. The options are to read dense handbooks provided by the payers with medical necessity criteria or to pay for software like Milliman Care Guidelines (MCG) and InterQual (owned by UnitedHealth Group ;) ) which provide checklists for medical necessity criteria.

Of course, the determination of where these guidelines come from are not made available to the public — because for some reason evidence based clinical best practices are considered proprietary and Aetna members supposedly have different anatomies than Cigna patients.

The process of evaluating these criteria is usually not even happening at the point of care. To approve outpatient procedures with prior authorization, what typically happens is that someone must receive a referral and go back-and-forth with the payer to submit the appropriate documentation for the approval. In one hospital I visited, there was an entire role in Patient Financial Services reviewing an inbox of faxed/scanned prior authorization letters from payers to determine whether patients had approval for lab tests. Without an approval, the patient could not be scheduled and it was evident that several patients had been waiting weeks for approval.

The situation is more dire for those seeking hospitalization. The same hospital had two utilization review nurses who spent all day reviewing patients with pending inpatient hospitalization approval. Payers often do not respond for 48-72 hours to requests for hospitalization — which is quite concerning considering that the patient needs care now.

While waiting, patients are by default admitted to observation status. Even if the approval comes in, the patient must be inpatient for 48 hours to be fully covered for the inpatient services. If a patient only needed 50 hours of inpatient hospitalization and had to wait 48 hours before getting the approval, there are only 2 hours left. Despite giving care for inpatient severity of care, the hospital can only be paid for 50 hours of observation services which is often a fraction of inpatient reimbursement rates.

In the event of a denial of medical necessity for inpatient hospitalization, the patient has likely gotten better than when they first came to the ER/direct admission. Vitals and other objective measures would not line up with criteria and the visit would still go entirely under observation reimbursement.

When I spoke to one of the UR nurses at the hospital, she also mentioned that despite meeting all listed criteria, patients will sometimes still be denied care for services. The case managers on the payers’ UM teams will sometimes cite criteria that are not listed in the guidelines. Clinicians working UM for payers don’t even always line up with the specialty of care for procedures they review. Nothing stops a gastroenterologist working for UnitedHealth from denying care for a lung collapse and citing their own clinical expertise.

The industry response as expected makes plenty of room for consultant work in this space. Another hospital I visited had hired consultants to train physicians on how to improve medical documentation to improve inpatient admission rates. It’s like hiring tutors for a standardized test — spending time and money to learn the rules of a system that does not even truly evaluate performance (in this case, the clinician choosing the most appropriate level of care).

Tech

So where does tech fit into all of this?

Undoubtedly, this is a manual process wherein technology can be used to achieve efficiency in submitting requests for authorization and quickly appealing approvals. It can pull medical documentation from a patient’s history, automate the process of navigating through the variety of payer web portals, use natural language processing to attempt to match criteria against data, and help prioritization of complex cases.

But the technology does nothing to stop the entrenched interest of the payer to deny care. Process automation can help overcome today’s hurdles in prior authorization and admission medical necessity, but nothing stops payers from adding news processes and guidelines in the future. Nothing stops UnitedHealth from telling UM case managers to consider extra unlisted criteria because their algorithm suggests a patient already got too many claims reimbursed for the year.

What is this supposed to achieve in a state of homeostasis? Providers and payers pouring billions into bots that are fighting each other on a process designed to prevent people from accessing healthcare services?

There exists a place for companies to automate the process of prior authorization today, but they will never solve the root issue. Tech influencers and venture capital need to back off of this problem space because the reality is that most of these people have never actually spoken to hospital case managers let alone understand what “managed care” is.

The worst part of this is hype cycle that many health tech companies end up taking significant venture funding or acquisition offers from health payers once they reach a critical mass of relevance. So then what? The payers control the UM process and the companies promising to alleviate the pain it causes providers? Unless there’s substantial advocacy for change in regulation surrounding UM, they’re just creating a niche industry of middlemen perpetuating a fundamentally unfair system.