Kaiser's History is Rhyming

Kaiser Permanente is clawing its way back to its past size

Acquisition and mergers leading to the consolidation of providers and payers is nothing new. It’s a trend as old as the explosion of healthcare expenditures year over year. Recently, Kaiser Permanente acquired Geisinger Health, an operator of hospitals based out of Pennsylvania. This play, to be operated under a subsidiary named Risant Health, is Kaiser’s response to a growing attention to “value-based” and “integrated” care in the modern healthcare ecosystem.

What’s particularly interesting is seeing how today’s strategy of expansion mirrors Kaiser's past when it pursued similar explosive growth to dominate the HMO market during the 70’s and 80’s.

This is the first in a multi-part series on Kaiser Permanente and its place in today’s complex healthcare provider and payer industry.

“Integrated” and “Value-Based Care”

Kaiser Permanente is most known for its model of “integrated care delivery” which has been grown alongside an American healthcare sensationalism around “value based care”. The premise is that healthcare costs have been driven up by providers being paid based on the amount of services they provide to patients. Reimbursing based on “value” as opposed to “volume” has been pushed as a way to deliver better care for patients with less “unnecessary” care.

Reimbursing on value means many things. Some providers may be given bonuses for clinical quality measures related to hospital readmissions or biometrics like HbA1c scores for diabetic patients. Other systems pay doctors fixed salaries to decouple physician incentives from the higher reimbursement of giving many services. I’m bundled payment models, physicians may be given a fixed payment for a medical treatment and long-term monitoring of the patient afterward as a way to incentive better care up front to reduce complications later.

Bundled payments and quality bonuses are likely to come from health plans, but one quirk of the integrated care model is the health plan’s ownership of the healthcare providers. On paper, this incentive of the health plan to reduce medical costs can be tied to the management of provider labor who can be better aligned to high quality care now to prevent costs later on.

Kaiser’s Story

Kaiser Permanente’s story predates the gradual shift to “managing care” and “value based care” that emerged from the 1980’s.

During the construction of the Colorado River Aqueduct in the Mojave Desert, Henry J Kaiser and a handful of other contractors established an insurance consortium to cover worker’s compensation needs of 5000 workers. Having recently finished his residency, in 1933, Sidney Garfield secured a contract to offer healthcare services out of a tiny hospital in Desert City, CA.

In trying to equip the hospital with enough resources to care for patients awaiting transport to Los Angeles and a desire to treat all patients regardless of an ability to pay, Garfield struggled to keep the hospital in healthy financial state. After winning over two executives of the insurance consortium, Garfield secured a contract wherein care for the workers was prepaid. His hospital earned $1.50 per worker per day, and soon he was able to pay off the hospital’s debts and grow a financial reserve.

In 1938, the Kaiser Company went on to acquire a new contract for the Grant Coulee Dam, in which it led another insurance consortium. Garfield was then brought on to replicate the Desert City model, this time covering care for workers and their families and transitioning from just industrial medicine to family practice.

To support the needs of 30,000 workers in Kaiser shipyards during the Second World War, Garfield continued building out and operating on this prepaid health delivery model. At the end of the war, Henry Kaiser and Garfield opened the Permanente Health Plan to members of the public, with membership quickly swelling to 300,000 across northern California driven by adoption by labor unions. This new integrated delivery organization was constituted of three parts — the health plan, the hospitals, and the physician group.

In an effort to capitalize on the name recognition of Kaiser Industries, the health plan and hospital group rebranded to Kaiser Foundation Health Plan and Kaiser Foundation Hospitals, respectively. Physicians resented the implication of being employed by Kaiser, thus the medical group remained the Permanente Medical Group. In combination, these three organizations manage care for members of Kaiser plans to this day.

Kaiser was a leading health maintenance organization (HMO) following the passage of the Health Maintenance Organization Act of 1973. As an HMO, members of Kaiser plans must receive referrals from primary care physicians to receive specialty care. Through reliance on primary care and a built-in control on the patients’ utilization of specialty care, the HMO can keep overall medical expenditures lower and offer lower out-of-pocket costs and premiums to plan members.

Interestingly, the American Medical Association (AMA) proved a bitter rival to the growth of Kaiser. The AMA, a national professional organization and lobbying group of physicians, promoted the expansion of preferred provider organizations (PPO’s) in opposition to HMO’s. PPO’s do not require primary care physicians for members and allow specialty care without referrals. These PPO plans also allow members to receive care outside of their network, even if at higher cost to health plan members overall.

Part of the reason Kaiser had to operate its own hospitals was actually because of this opposition to prepaid health plans and the HMO’s they eventually turned into. The state board of medical examiners had Garfield’s license revoked for “unprofessional conduct” before courts overturned this measure. In many cases, physicians in prepaid plans were barred by local medical societies and hospitals from practicing. Some academics argue this intense opposition to the spread of HMO-like plans was because prepaid health plans with fixed payments to physicians threatened to remove the power of practitioners to adjust charges to the income of their patients.

Rising Competition and Risant Health

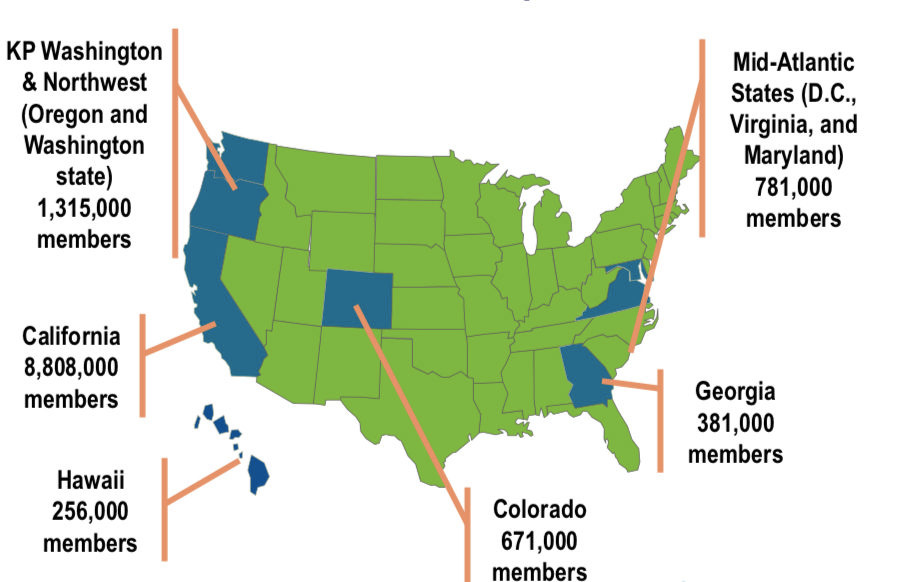

Kaiser expanded its footprint beyond the Pacific coast rapidly through the 1970’s and 1980’s — states like Hawaii, Colorado, Ohio, Texas, Georgia, Connecticut, North Carolina, and the Washington D.C. saw a new presence. It is believed that this strategy of expanding across the country was to establish large-enough corporate accounts and national presence to have a seat at the table in the event health reform legislation made its way through the federal government.

Many of these efforts were unprofitable and eventually closed or sold off. Texas was sold off in 1998 followed by the sale of the Northeast division in 2000. Catholic Health Partners bought the Ohio division in 2013. More violently, the North Carolina operations out of Raleigh-Durham had to be closed altogether.

Unlike California and cities in the Pacific Northwest, many of these other geographies did not have sufficient population density to make a highly coordinated and managed network of care very suitable. Residents of these areas were also not very familiar with (or accepting of) the lack of an ability to receive care out of what was considered a very small network by the standards of other local PPO’s.

The past several years have seen other health systems like HCA, Trinity, and Ascension pursue aggressive acquisition of hospitals across the country. A smaller number of these systems have adopted a similar model of integrated care as Kaiser, but some notable examples include Intermountain Health headquartered in Salt Lake City, UT and Geisinger Health, the most recent acquisition of Kaiser.

As we continue to look into the future of Kaiser Permanente and how it wants to define its place in the space of interstate health systems, it’s critical to consider at what point it would constitute a repeat of the missteps of the 1970’s when growth-at-all-costs was pursued only to fall apart when facing the realities of a business model incompatible with local healthcare delivery needs and norms.

Much of the expansions today focus on how value-based care may change the underlying economics of care delivery. Making a bundled payment profitable requires delivering less services overall but with high enough quality that it prevents complications later on, and the bet players like Kaiser are making is that integrated and large consolidated players like themselves have the best resources to coordinate care and control costs. Whether local providers are willing to join such networks and play by the rules of a more controlling health system is a question to be answered.

Fascinating story, thanks for sharing. I keep thinking about the illusion of choice these insurance plans create for the patients! I wonder if an individual patient has any leverage at all. Employer paid plans are also becoming more expensive for individuals, with higher deductibles and out of pocket payments. And still we keep asking why healthcare costs are so high. I would love to learn more about the power dynamic in the entire healthcare delivery chain, including manufactures.