Federalism, Pensions, and Health Insurance

What is ERISA, the biggest private health insurance law, all about?

When you dig into healthcare legislation and regulations, a word salad of a law is often mentioned. Consider the February 2022 Senate bill named the Affordable Insulin Now Act, which would have capped out-of-pocket insulin costs for all insured Americans at $35. This bill proposed amendment to a law called the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 (ERISA), and it was no small addition.

The amendment would have applied the $35 limit to any “group health plan or health insurance issuer offering group health insurance”.

This short-lived bill is not the only appearance of ERISA. Landmark laws like the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) and Affordable Care Act (ACA) mention and amend ERISA. Through the subtleties of complex federal regulation oriented at large employers, ERISA has not only become a key policy tool to regulate private insurance but has also shaped the structure of these private companies themselves and debates around how to regulate them.

Constitutional Law and the Power to Regulate

Before diving into the significance of ERISA, it’s important to understand that the federal government’s ability to regulate the economy is restricted to powers that is has under the Constitution. Unlike the state governments, federal legislation cannot do things like impose rent controls on all landlords, set education curriculum standards, or directly impose rules on what every health plan must administer. The federal bureaucracy gets most of its powers from Congress delegating its powers to the executive branch of government.

When you look into the language of an executive order, you’ll notice that it almost always specifically cites some piece of legislation from Congress that was signed into law. If the Department of Commerce imposes tariffs on steel, it’s probably doing so under the authority of the Trade Act of 1974. When the President authorizes air strikes on a country for which there is no authorization of force from Congress, it’s probably under the guidelines of the War Powers Act. This is also where we see the distinction between federal legislation and regulation.

Whereas legislation is written and passed by Congress, it often leaves many specifics up to the executive branch to detail through regulation. The idea is that the executive branch, under the control of the President, can move much faster than Congress to enact changes in rules. Delegating the fine details of trade policy and national security, for example, lets Congress delegate this work to the federal bureaucracy which theoretically does not need to get involved in politics to move quickly on new developments. It also means that members of Congress don’t need to be experts on everything, because someone in some federal agency can take responsibility.

For example, when the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) updates rules, it’s updating existing regulations that apply to laws like the Affordable Care Act (ACA), Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), or Social Security Act (SSA).

One of the primary ways that the federal government gets around constitutional limits to regulate industries is with the Commerce Clause, which gives Congress the authority to regulate business across state lines. In combination with the Power of the Purse, to set tax policy and spend that revenue, we see the legal justification for what would become ERISA. However, the efforts of federal legislation to regulate certain industries against a singular standard often conflict with intentions to regulate at the state-level.

Pensions and Welfare Plans

Triggered by price controls during World War II, many employers started offering health insurance benefits to employees. Through the 1960’s, most government regulation on these plans’ structure came from state governments. Such health insurance mandates from the state could require insurers to cover certain groups of people or certain types of healthcare services. At this time, large employers with employees in multiple states had to manage the different sets of state-level insurance mandates. The collective power of these large actors were successful in stonewalling many proposed state-level insurance mandates before 1974.

A pension reform law would radically change that.

In 1963, automotive manufacturer Studebaker shuttered a manufacturing plant in South Bend, Indiana. Due to mismanagement of funds, the thousands of retirees and workers of the plan found that their former employer could not fulfill promises of the pension plan. The 3,600 workers past retirement age received their full pension benefits, but 4,000 workers received only 15% of their promised pension, and another 2,900 received no pension at all. It fueled growing calls for pension reform and spurred a Congressional investigation into management of pension funds by employers and unions. Later in the decade, Senator Jacob Javitz introduced a bill for pension reform in 1967.

The final law enacted in 1974 imposed significant rules on pension plans under private employers to report financial information and standards of conduct. To help provide benefits to members of pensions with insufficient assets, the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation (PBGC) acts as an insurance fund. Today it covers 26,000 pension plans in the country.

More relevant to health insurance, ERISA also regulated “welfare plans” including health insurance that were self-funded, meaning that the employer covered the cost of health claims of employees in the plan. Employers spanning multiple states with self-funded health plans could now only be subject to ERISA, which preempted local state regulations and allowed employers to avoid state-level restrictions and taxes. By giving these large employers a means to avoid 2-4% taxes on health insurance premiums paid by employees and a way to enjoy the more consistent rules of federal health insurance regulation, many employers adopted self-funded plans.

New Rules, New Players

Before, many employers were paying premiums to a large health insurer to manage the health plan, but ERISA gave new incentives to bring administration of health insurance in-house as a way to cut costs.

A new niche of health insurance called the third-party administrator (TPA) exploded. These TPAs handled management of medical claims for self-funded health plans. Large insurers, seeking to capitalize on the growth of self-funded plans, launched a similar set of businesses including administrative services only (ASOs).

By 2017, almost 60% of insured employees were under self-funded plans regulated by ERISA. With large employers no longer impacted as significantly by state-level health insurance regulations, the number of such mandates increased after the passage of ERISA, imposing rules on how in-state health plans had to operate.

Because of how ERISA is fundamentally tied into the regulation of large employer-sponsored insurance, a number of landmark healthcare laws amended ERISA. The Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1985 (COBRA) created rules which allowed employees to continue health coverage for some time after events like loss of employment while the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) imposed limits on how health plans could discriminate on certain health status information.

Tug of War

We come back to the issue of constitutional law, because current debates about ERISA revolve around how much the federal law can preempt state regulation. Through preemption, federal rules essentially overrule any local laws concerning these self-funded health plans.

Originally, the legal “test” for whether state laws were preempted by federal law considered whether the state law had “a connection with, or reference to, covered employee benefit plans.” This was broad language that essentially prevented any sort of state regulation remotely related to self-funded plans under ERISA until three notable cases made their way to the Supreme Court.

New York State Conference of Blue Cross & Blue Shield v. Travelers Insurance Co (1995), California Div. of Labor Standards Enforcement v. Dillingham Constr., N.A. (1997) and De Buono v. NYSA-ILA Medical and Clinical Services Fund (1997) changed that test so that only state laws mandating changes to the health plan structure or administration would be preempted.

The Travelers Court noted that nothing about the ERISA or its legislative history “indicates that Congress chose to displace general health care regulations, which historically has been a matter of local concern.”

“The Preemption Clause That Swallowed Health Care: How ERISA Litigation Threatens State Health Policy Efforts” - Health Affairs

An all-payer claims database (APCD) is a state-run database of health insurance claims intended to support research and transparency concerning utilization, quality, and pricing of healthcare services. Many health insurers are reluctant to hand over this type of data, so many states passed regulations to mandate that payers send this data to state-run APCDs.

In 2016, the Supreme Court saw Gobeille v. Liberty Mutual Insurance wherein Liberty Mutual was disputing a Vermont law which required all health plans to send claims data to the APCD. As it turns out, the opinion of a court changes with new justices, and the court seemingly changed its stance, arguing that the Vermont law prevented ERISA from imposing its “single uniform national scheme for the administration of ERISA plans without interference from laws of the several States even when those laws, to a large extent, impose parallel requirements.”

The case allowed many employer self-funded plans to hide behind ERISA to fight a variety of state health regulations. Some APCDs lost almost 30% of their claims data because of the ruling while employers fought states on other policy like healthcare pricing transparency.

However, in 2020, the Supreme Court upheld the status of Arkansas Act 900 in Rutledge v. Pharmaceutical Care Management Association. The Arkansas law regulated pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) which work closely with health plans to manage coverage of drugs in pharmacies. Under the regulation, PBMs had to pay pharmacies a minimum cost for generic drugs to ensure that rural and independent pharmacies could justify keeping generic drugs in stock. The PCMA, a PBM trade group with members losing money on supplying these pharmacies with generic drugs, sought to argue that the state law was preempted by ERISA.

Despite ruling in favor of PBMs at the district courts, the Supreme Court argued that PBMs were not covered under ERISA and that this cost regulation did not impact the choices made by self-funded health plans.

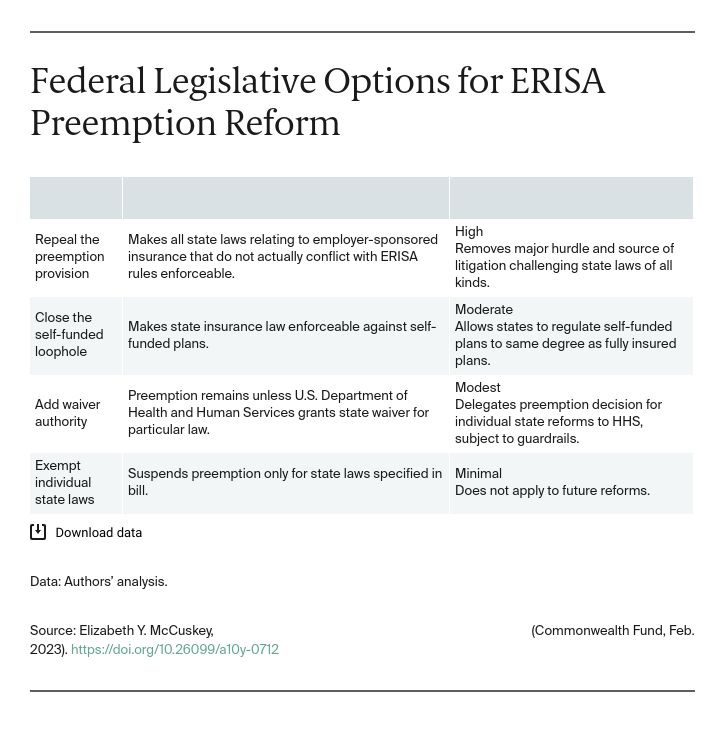

These legal uncertainties have raised questions about how to amend ERISA’s preemption clause to draw a clearer line in the sand on how the states can regulate health plans. The current preemption law does not even allow the Department of Labor to make waivers to remove preemption for certain state-level reforms. The stakes for preemption go beyond just APCDs and reporting on prices of healthcare services.

Such restrictions on state authority to regulate health plans means that the states cannot create stronger laws to mediate the disputes between health plans and hospitals that leave patients to suffer with hefty surprise bills. Reforms on prior authorization are also limited, because large health plans can simply skirt requirements to be more transparent to providers about reasons for denials and make the process easier to complete. That’s of course not to mention regulations that could require inclusion of certain preventative/diagnostic services, dental or vision benefits, and mental health services.