A Power Shift From from Healthcare Experts to Lawyers

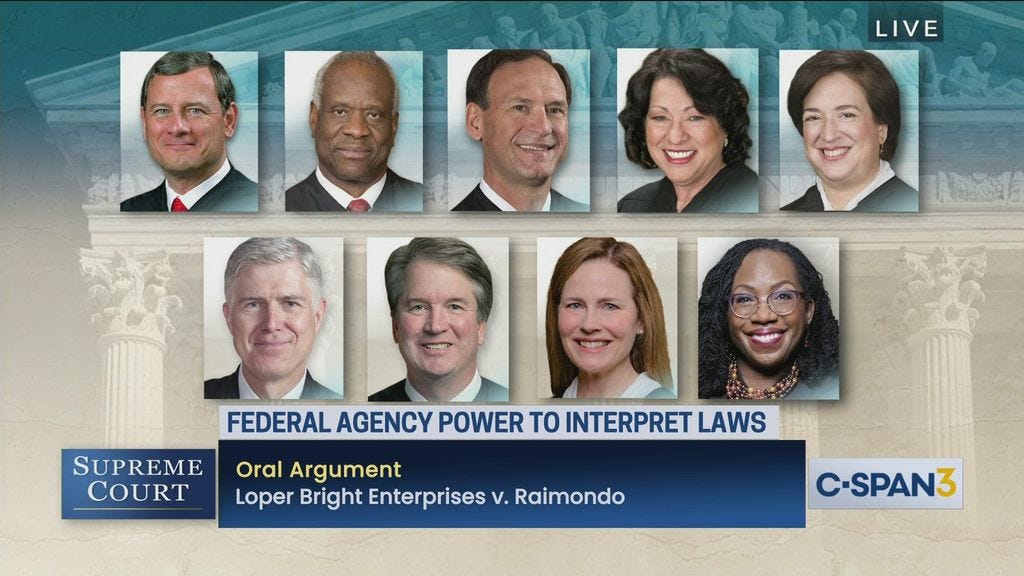

Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo overturned the Chevron deference. Here’s what that means for healthcare

Every summer brings a new slate of Supreme Court decisions which each have cascading impacts through the country. Judicial review allows laws and legal doctrines to be entirely overturned — leaving room for challenges to other laws in lower courts, causing realignment of legislative priorities or strategy, and reinterpretation of long-standing legislation and Constitutional law.

Healthcare is no where near immune. With the massive involvement of the state and federal governments in programs like Medicare, Medicaid, CHIP, and a never ending alphabet soup of agencies, changes to SCOTUS’ interpretations drive the direction of health policy and the multi-trillion dollar business of healthcare delivery.

Lower Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo initially concerned the regulation of fisheries. Its decision — which included the court ruling to overturn the so-called Chevron doctrine — has monumental impact on healthcare regulation. The ruling leaves much of the federal administrative agencies’ regulations up for court challenge which in effect defangs the federal government extensively.

Laws and Regulations

Although they seemingly get used interchangeably, there is a significant distinction between the terms law and regulation.

Laws are passed by Congress and signed into law by the President. These include the national mandate which raised the drinking age to 21 and the Affordable Care Act (ACA), which expanded the Medicaid program and established regulated insurance marketplaces, and among other items in a lengthy list of reforms to insurance policy.

The executive branch under the President needs resourcing and staff to enforce the laws created by Congress. Agencies and administrations like the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) are funded by Congress and typically under the direction of the President to enable the execution of laws in areas such as health coverage and antitrust, respectively. These agencies, as long as they work within the constraints imposed by laws (also called statue), have broad authority to make rules and issue formal interpretations of law.

It’s important to note that typically, Congress does not have the time or expertise to get into the weeds of complex areas of policy like environmental or public health. Coupled with political gridlock, a system where every federal policy requires passage as law by Congress could make the federal government too slow to respond to complex issues or fast-emerging topics — from the safety of clinical use-cases for AI to extending billing flexibilities that can allow rural providers to stay afloat.

In fact, a host of laws feature Congress delegating its authority to regulate certain areas of policy to the executive branch with an understanding that Congress simply cannot move as fast as agencies and bodies staffed by policy experts under the direction of the Presidency.

The War Powers Act, for example, gives the President the permission to temporarily initiate military action without Congressional approval. The President must then go before Congress to explain the use of force and ask for extensions to the temporary delegation of power to command undeclared wars — unless Congress is so hawkish that it outright declares war.

As a delegating body, in many of these same laws, Congress can revoke those powers through new legislation. Congress further exercises influence via political appointments for these administrative agencies, which the Senate must confirm.

The rules and policy enacted by these agencies are all regulations. When reading the fine print of laws and regulation, this distinction is clear. Whereas legislation cites the powers Congress derives from the Constitution, regulations typically cite laws indicating where an agency derives its authority.

The Administrative State

The Great Depression and Franklin Roosevelt’s landslide election victories transformed the trajectory of the US federal government. FDR’s New Deal and the war economy which fully pulled the country out of the Depression was Keynesianism on full display — a school of economic thought which concerns how government interventions can mitigate volatility in the economy.

To execute these new programs and regulations spanning labor, banking, and agriculture (to name a few areas), the powers of administrative agencies grew significantly. Through tough battles with the Supreme Court and Congress, many of these programs and their agencies lasted through the Second World War. However, the growth of these agencies required some legislative response to establish guidelines preventing the overreach the powers of these agencies’ Constitutional authority (and to appease opponents from the aforementioned political fights). The Administrative Procedure Act (APA) was this response.

The APA was the compromise between the New Deal coalition and skeptics of growing federal involvement in industry. It set rules about how administrative agencies must allow for public input (for example CMS public comment periods), required agencies to inform the public about policies, and established standard rulemaking processes for these agencies.

Most important to Loper Bright Enterprises v Raimondo is the APA’s assertion that the court system is to to review matters of legal dispute.

Chevron

The Chevron deference comes from the 1984 Supreme Court ruling in Chevron U.S.A., Inc. v. Natural Resources Defense Council, Inc. This case was sparked by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) redefining the regulatory interpretation of a “source” of pollution under the Clean Air Act. The Natural Resources Defense Council, an environmentalist group concerned that the redefinition paved a way for polluters to skirt EPA environmental review processes on plant upgrades, sued that Congress did not authorize the EPA such discretion over the definition of a “source”.

NRDC was successful when it filed a petition for review in a lower district court. Future SCOTUS justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg authored an opinion that the EPA’s new definition conflicted with other definitions of “source” established in previous cases.

Chevron, which stood to benefit from the new definition appealed the lower court’s decision. Ultimately, SCOTUS sided with the EPA and Chevron, saying that courts should defer the ambiguity of the definition of “source” to the EPA.

“If Congress has explicitly left a gap for the agency to fill, there is an express delegation of authority to the agency to elucidate a specific provision of the statute by regulation.”

Chevron, 467 U.S. at 843–44

The Chevron deference, as it would be named, became a two-step legal test for whether to defer to agency interpretations of law. These steps were to verify that Congressional text specifically addressed an issue at hand and whether the agency’s answer was made on a “permissible construction” of law. The purpose of this two-step test was to address a concern that arose in three related cases from lower district courts.

The three cases arrived at different conclusions, not through review of the explicit law, “but on their own views of whether each program’s policy was to enhance or merely to maintain air quality”, according to a review of case law submitted by NRDC during the proceedings of Loper. This summary further notes that this the EPA’s intents were being replaced by judges’ personal policy preferences — violating the independent role of the court system and as with this case, causing conflicting rulings.

It’s not surprising that the Chevron deference, created to prevent policy preferences from overriding agency authority, would be weakened (West Virginia v EPA, 2022) and eventually overturned (Loper) by an increasingly partisan court.

Some observations in rural healthcare

By taking the administrative agencies’ power to interpret and clarify ambiguity in laws, the Supreme Court has opened the floodgates for overturning dozens of healthcare cases in recent memory, while opening up other policies to lawsuit.

From the libertarian perspective, this is the Supreme Court reigning in an administrative state which has made itself obstructive and potentially abusive to providers, payers, and patients. The point of this post is not to refute that statement by providing the laundry list of abuses perpetuated by bad-faith actors in every corner of healthcare. Rather, it may be more convincing to tie this into two areas of observation I have made working with providers of rural and underserved populations.

The fundamental issue from the perspective of rural healthcare is the pure confusion that this decision can drive. These organizations, operating on slim margins and even slimmer staffing, generally work to stay clear of legal ambiguity. One audit or court ruling gone wrong can derail an entire line of service and jeopardize survival.

There’s also the fact that this may drive an unprecedented amount of flip-flopping in policy. The rules under a presidential administration will tend to remain uniform — at least until someone else comes into office and has their political appointments change agency priorities. Lawyers of various companies, on the other hand, can file lawsuits each and every year.

This decision, which allows a great deal of healthcare regulation to come under fire, means that organizations which are already fairly conservative in interpretations of regulation must work within tighter guardrails that they may be unable to quickly adapt to — let alone have legal help to stay on top of these changes to policy intricacies.

Making Telehealth a Sustainable Operation for Providers

Rural providers understand that telehealth can be the best way to maximize patient engagement in settings where travel distances are long and exacerbate existing impediments to access to care. In other settings, telehealth can enable access to much-need specialty care such as through North Carolina’s Statewide Telepyschiatry Program (NC STeP), which connects patients in rural emergency rooms to psychiatrists. Engaging patients and letting them easily access care ensures that providers can meet community needs while ensuring they have sufficient volume of billable services to stay open.

However, the financial side of this equation remains the greatest obstacle to expansion of independent providers’ ability to provide this care.

Rural Health Clinics (RHCs) through the end of 2024 have the permission to bill for these telehealth services, but only under a CMS waiver. These waivers, which allow even Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs) to bill for telehealth temporarily, can entirely come under fire by other types of providers, because RHCs and FQHCs are not explicitly mentioned in telehealth laws.

For providers of rural and underserved areas, as most RHCs and FQHCs are, CMS has also provided flexibilities to the definition of “telehealth services”. For example, it allows providers to occasionally conduct audio-only services and for other providers has listed communication technology-based service codes (CTBS). All are fair game for review, and ultimately, could discourage continued adoption of telehealth by these providers.

Access to Prescription Drugs for Patients with Financial Hardship

Recently, a South Carolina FQHC by the name of Genesis Healthcare became the talk of 340B operations. The 340B drug pricing program is named after section 340B of the Public Health Service Act, which requires that pharmaceutical companies covered by Medicaid must provided discounted outpatient prescription drugs to providers serving largely disadvantaged populations — including Critical Access Hospitals (CAHs), FQHCs, and Sole Community Hospitals (SCHs).

Genesis in 2017 had failed an audit by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), which had alleged that the FQHC used the 340B program to obtain drugs for patients that did not fall under HRSA’s interpretation of a 340B “patient”. The federal district court struck down HRSA’s specific language, and the broadened definition opened the floodgates to health systems and 340B vendors reaching more patients and expanding this profitable service line.

Is it so difficult to see how a health system losing patients to a small CAH capturing market share with its own discounted drug access may fight for a redefinition of “patient” in the courts?

There’s also matters of eligibility. I’ve worked with a rural hospital which was in the midst of implementing 340B, only to find after a CMS cost report submission that it was suddenly ineligible for the program. The opportunity for criteria to change because lawyers can sway some judges may lead to some providers holding off on 340B — which inevitably means low-income patients cannot get access to discounted prescription drugs.

Clearly, there are more areas of concern. Some include but are not limited to….

definitions of allowable family planning services (including abortion care)

safe access to care for LGBTQ+ patients

scope of care for different types of providers like Registered Nurses

staffing requirements for hospice and nursing facility care

rules to prevent information blocking and support interoperability

price transparency rules for hospitals and payers

All that can be said for sure is that the road will probably be quite bumpy in the coming years as the overturning of Chevron ripples through the Federal Register.